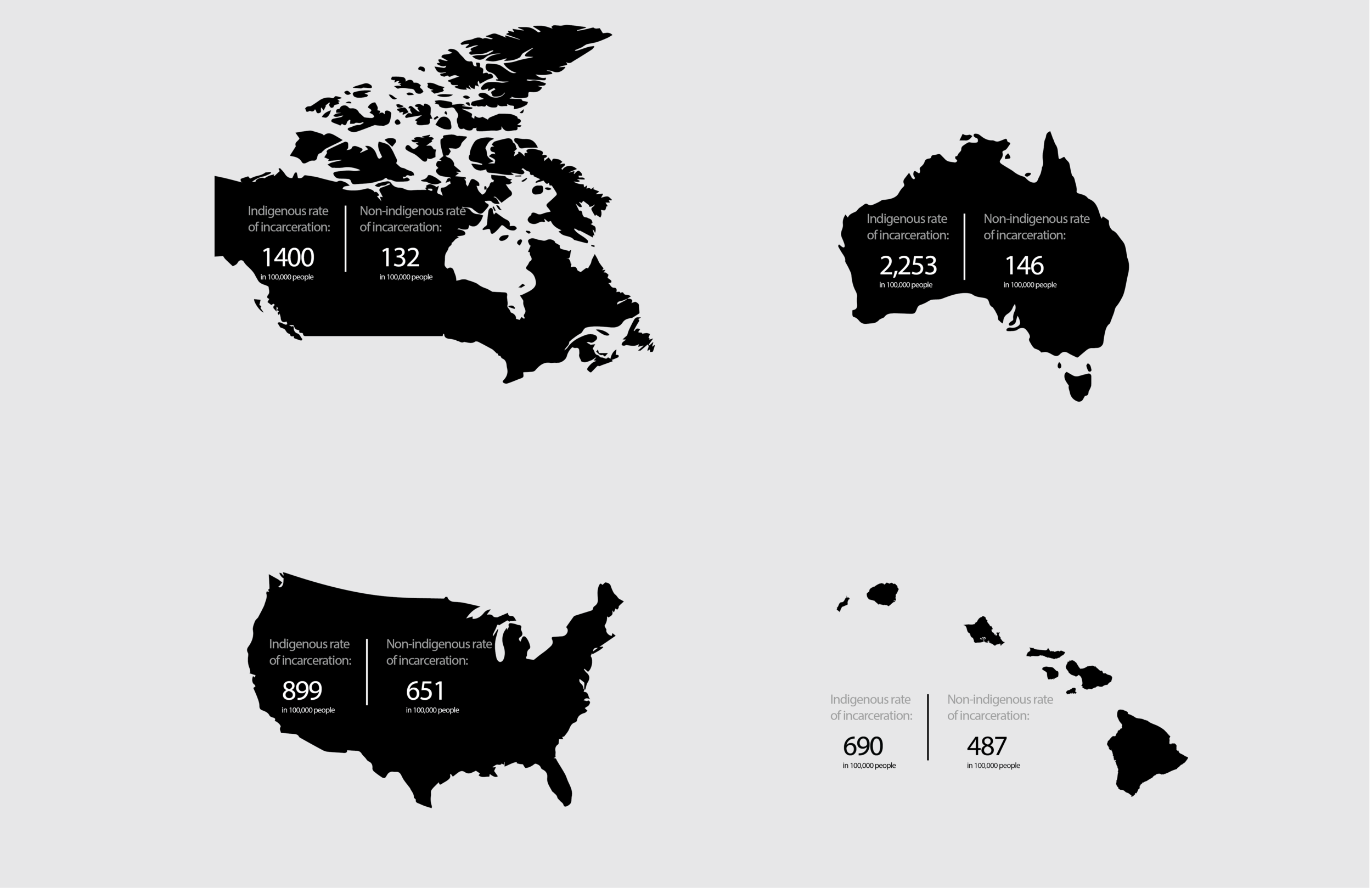

Indigenous peoples make up a disproportionately high percentage of the world’s prison populations.

“In 1991 indigenous peoples accounted for less than 2.0 percent of the total population of Australia, yet 14 per cent of all adult prisoners were indigenous . . . In Canada, indigenous offenders represented 16.6 per cent of the federal prison population, while comprising only 3.38 per cent of the Canadian general population, making indigenous Canadians 5 times more likely to be imprisoned, than their non-indigenous fellow Canadians . . . In New Zealand, of 10,452 cases resulting in a custodial sentence in 2005, 5,293, or just over 50 per cent, were Maori. Sixty-one per cent of women sentenced to prison in New Zealand in 2005 were Maori. Ten years earlier, Maori women were 49.3 per cent of sentenced inmates and Maori men were 45 per cent of sentenced inmates. In 2006, the Maori were 14.6 per cent of the total population, making them 3.4 times more likely to be imprisoned, than non-indigenous New Zealanders.”

—State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples (2009)

“For the last two centuries, the criminal justice system has negatively impacted Native Hawaiians in ways no other ethnic group has experienced . . .”

”. . . to reduce the harmful effects of the criminal justice system on Native Hawaiians and all people, Hawai‘i must take action, and seek alternative solutions to prison. Assistance and training is needed in law enforcement, holistic interventions need to be implemented and evaluated, and a cultural shift in the way we imprison a person must change. If not, we will exacerbate prison over-crowding, and continue to foster the incarceration of generations to come.”

—The Disparate Treatment of Native Hawaiians in the Criminal Justice System (2010)

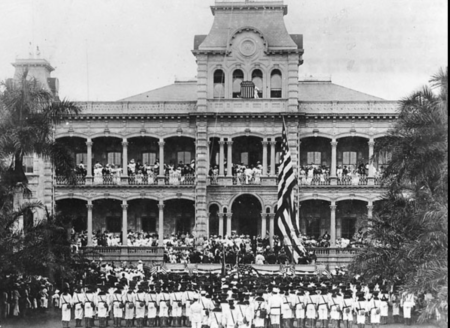

From first contact by non-islanders in 1778, through the armed overthrow of the independent Hawaiian monarchy in 1893, including Hawaii’s subsequent incorporation by the United States, Native Hawaiians have struggled to survive.

The loss of sovereignty has framed successive waves of missionaries, settlers, laborers, businessmen, and military personnel, whose appropriation of power and land further imperiled Native Hawaiian language, practices, and identity, subjugating and trivializing indigenous culture. Along with other Pacific Islanders, Native Hawaiians still struggle against systemic racism, poverty, homelessness, and poor health.

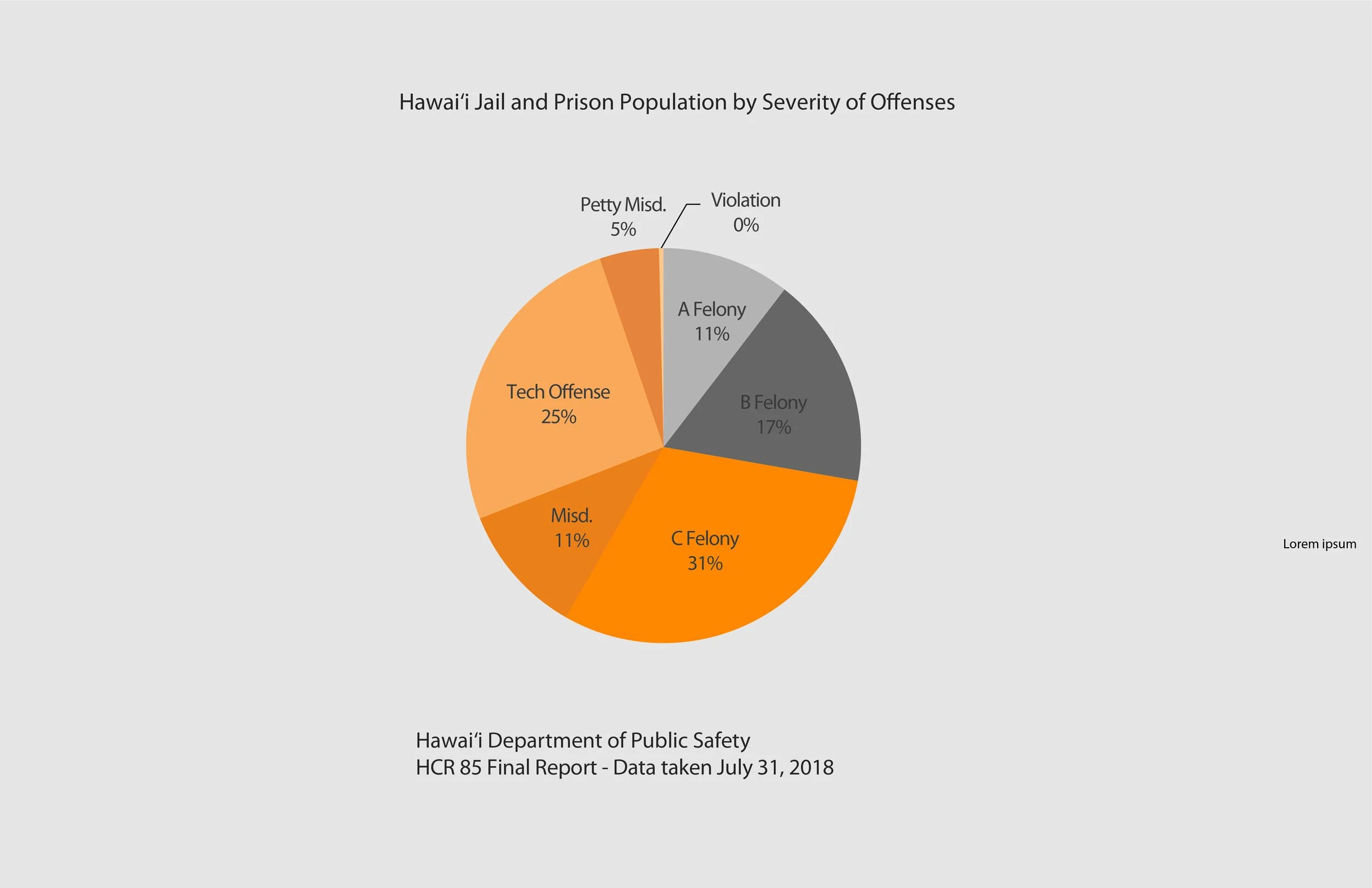

“Many people believe that Hawaiʻi’s prisons are filled with extremely dangerous and violent prisoners, but that is a misconception.”

“The vast majority (72%) are incarcerated for relatively low-level offenses, i.e., class C felonies or below (misdemeanors, petty misdemeanors, technical offenses, or violations). Only 28% are serving sentences for the more serious class A and B felonies, and not all of the A and B felonies are for violent crimes, many are for drug offenses. Additionally, 53% of Hawaiʻi prisoners are classified as minimum or community custody inmates.”

—Creating Better Outcomes, Safer Communities: Final Report of the HCR 85 Task Force (2018)

“Hawaiʻi could significantly reduce its prison population by diverting low-level offenders to treatment programs . . .”

”. . . such as diverting individuals with mental health and substance abuse issues to alternative facilities; finding alternatives to bail for individuals who can be safely supervised in the community while awaiting trial; having expedited hearings for prisoners who are jailed for technical probation and parole violations; expediting indigence screening and program referrals; issuing citations for low-level offenses instead of arrest and jail; and offering individuals charged with low-level, non-violent offenses the option of being adjudicated in community courts instead of in the criminal justice system.”

—Creating Better Outcomes, Safer Communities: Final Report of the HCR 85 Task Force (2018)

“The State is moving ahead with plans to build a 1,380-bed jail to replace the current Oahu Community Correction Center.”

“Planning for the new jail should focus on diverting low-level, non-violent offenders away from the criminal justice system, reforming the bail system to significantly reduce the number of pretrial detainees who remain in jail pending trial, reducing the jail population by eliminating short jail sentences in favor of community-based alternatives, housing the mentally ill in a separate facility where they can be cared for by mental health professionals rather than correctional officers, and creating alternative housing for sanctioned HOPE Probation violators and low-risk parole violators.”

—Creating Better Outcomes, Safer Communities: Final Report of the HCR 85 Task Force (2018)

“As of July 31, 2018 Hawai‘i had 1,347 prisoners at the Saguaro Correctional Center in Eloy, Arizona.”

“…the costs of private imprisonment are more than merely financial, because relying on mainland prisons severs an inmate’s family ties, undermines rehabilitation, and decreases the odds of successful employment after release.”

—Creating Better Outcomes, Safer Communities: Final Report of the HCR 85 Task Force (2018)

Image courtesy of XXX

“Treatment courts are an effective and efficient way to reduce the prison population and recidivism rate.”

“Studies have shown, for example, that drug courts reduce crime, make communities safer, save money, ensure compliance, combat addiction, and reunite families . . . Hawaiʻi currently has treatment courts that deal with mental health issues, addiction, and the problems faced by veterans. The Office of Hawaiian Affairs has been working with the Judiciary on the creation of a cultural treatment court that would focus on diverting individuals to programs with a rich Native Hawaiian cultural component.”

—Creating Better Outcomes, Safer Communities: Final Report of the HCR 85 Task Force (2018)

“Hawai’i does not have an effective support system for prisoners reentering the community.”

Upon release, the report recommends that each reentering individual should have ”(1) a decent place to live; (2) a state identification card, a social security card, and a birth certificate; (3) health insurance and, if necessary, financial assistance benefits; (4) employment if the individual is employable; (5) ongoing addiction and/or mental health treatment; and (6) access to wellness centers rooted in Native Hawaiian values.”

—Creating Better Outcomes, Safer Communities: Final Report of the HCR 85 Task Force (2018)

The YWCA Fernhurst Ka Hale Ho‘āla Hou No Nā Wāhine demonstrates the potential of new models for diversion, reentry, and transitional housing.

“The community-based furlough program works with women who are between a year and 6 months of being released on parole or completion of their sentence”… “the Fernhurst program is rooted in over twenty-five years of experience working with justice-involved women. The small size of the program allows the model to be flexible and adaptive as the needs of the women served change. Community partnerships are critical to the program’s success and involve health care, mentoring, apprenticeships, and access to positive social networks.”

—Creating Better Outcomes, Safer Communities: Final Report of the HCR 85 Task Force (2018)

Image courtesy of YWCA O’ahu

“Hawai‘i [must] adopt a new vision for corrections and repatriate traditional Hawaiian cultural practices that can restore harmony with ʻohana (family), community, akua (spirit), and ʻāina (land).”

“Only by supporting intrapersonal healing can we successfully reintegrate paʻahao (prisoners) and break the intergenerational cycle of incarceration.”

—Creating Better Outcomes, Safer Communities: Final Report of the HCR 85 Task Force (2018)

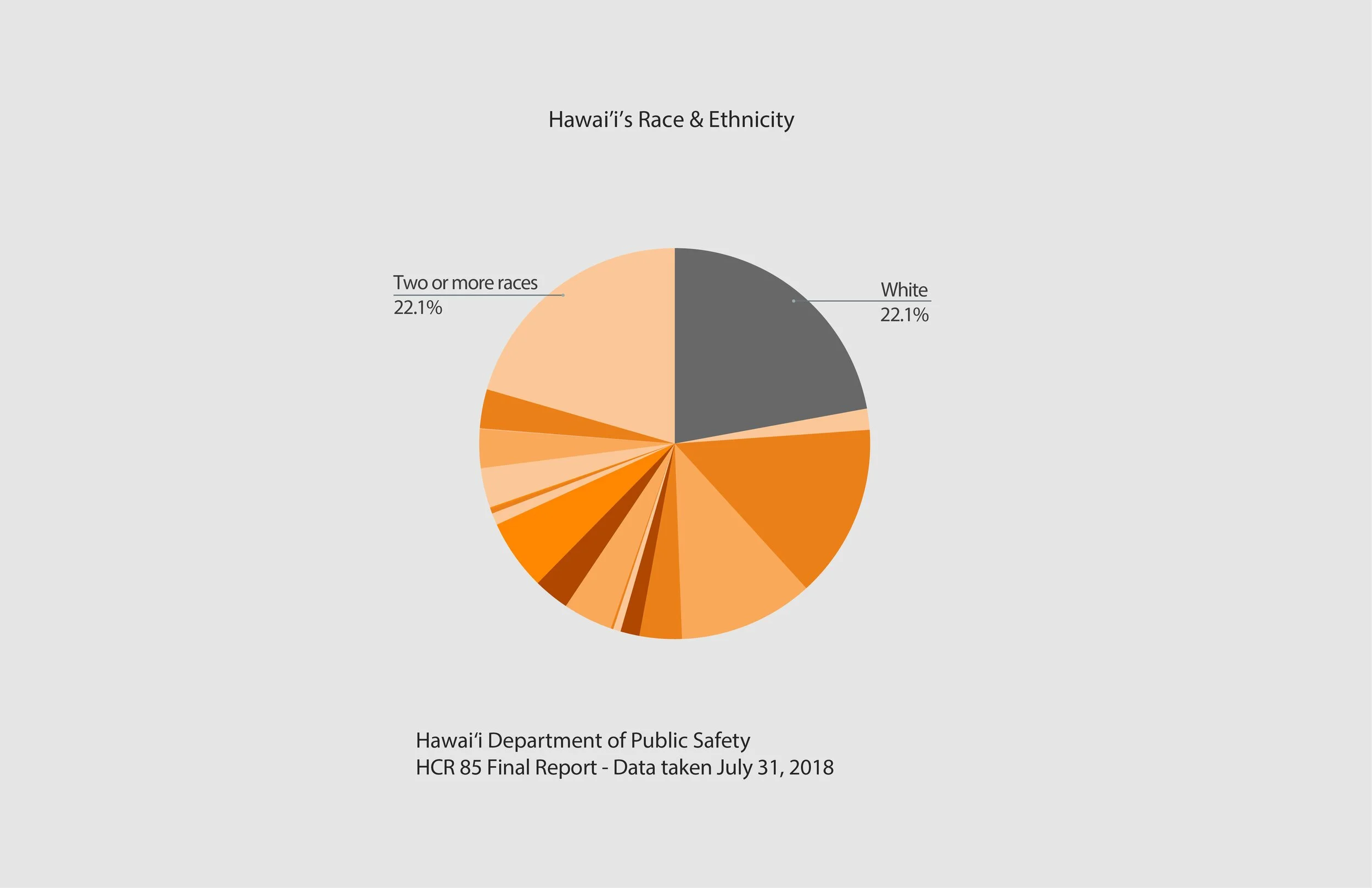

Our vision for criminal justice reform in Hawai’i offers the world a new model for multi-racial equity.

Hawaiʻi has the highest racial minority population of any state in the union — 75 percent, according to U.S. census figures.